A Life Lived Well / By ZeePack Friday, I took a call from Romy, my former hairdresser. She sounded distraught. “Are you all right? Are you depressed? I have not seen you since September.” There was urgency in her voice. I reminded her that the message I left on her answer machine told her I had cut off all her colors. As I admitted in my February 11 posting “Hair: My Croning Glory,” I knew Romy’s intent had always been to make me worthy of what she called my youthful energy. Yet I felt I had acted cowardly when I hadn’t respond to Romy in person and told her my reason for not scheduling a cut or color since September. I was afraid to tell her outright of my aim to be less vain. I failed to say I wasn’t willing to have her commandeer my head, deciding what style and colors would suit me best. After all, she was the professional, and when I sat in her chair I belonged to her from the neck up. Although on several occasions she had strong ideas about necklines, jewelry, and shoes. I thought that my voice mail response to Romy’s initial call meant that it was over. When I saw her name on my phone on Friday, I took a deep breath and bravely took the call. I could hear the disdain in her voice when she referenced the fact that someone else had cut off her creation. “What did you pay for that hair cut? Twenty dollars?” I told her the cost of the cut. But what I didn’t say was that not arguing or defending myself against pressure from a self-assured, aggressive hair stylist was priceless. While I would gladly have paid less — I am on a fixed income after all — I had not searched out a different stylist to save money at Romy’s expense. “You still need a good haircut no matter what color your hair is,” she said, seeming to dismiss the worthiness of anyone else’s scissor skills. “I’ll cut your hair for nothing. I miss you.” “I miss you too, Romy,” I said. I did not say I was not in the mood to be pressured. Instead, I did what I often do when clearly outmatched in aggression — I demonstrated canine courage by cowering submissively. “I have become a recluse,” I lied. “I knew it,” she said, a potential triumph clearly in view. Romy to the rescue! I heard and appreciated her worry and felt her relief that neither hate nor error on her part had contributed to my disappearing from her appointment book. She sounded eager to see me soon, insisting in the course of our conversation I book an appointment. If I heard her clearly, she would not sleep well until I let her look at me. I assured her I would definitely drop by. I did not say I would make an appointment. With deep sincerity she promised that she would not, definitely not, try to talk me out of the way I chose to look. Indeed, her last words before the phone call ended were “I promise (with a special emphasis on the promise) not to try and talk you out of your decision.” Within seconds of our heartfelt goodbyes and her repeated reassurances, the phone rang again. It was Romy. “But if I want to put in one streak, one silly streak, would that be all right? I won’t charge you for it.” After a long pause, I answered her.

From a collage by Susan Miller / Alison R. To make a susan shaped space is to mark off in your heart those parts of you that would be different or less had you not had a friend like Susan Miller in your life.

Sunday, the Mothertongue Feminist Theater Collective put on a celebration ceremony honoring Susan (Shoshanna) Merilyn Miller for women who knew and valued her friendship. As part of the program Lori Rillera sang “my miracle,” a song she wrote to express her deep affection for this woman who had been old enough to be her mother.

”I’m thinking of you

there’s a

susan shaped space

filled in my heart

you’re here

when I sing

and laugh

and dance

and make art”

Lori said that Susan would say to her that she was the same age as the daughter she gave up for adoption.

Alhough I did not know Susan well, I had been to some of the same gatherings and had followed the progression of her illness through postings by her good friends Corky Wick and Lori. They, with Susan, were members of Mothertongue with whom she had performed her written pieces about women’s experiences for more than 25 years.

Taken from venues where Susan is said to have read them animatedly, about 30 pieces were arranged to be read and filmed on Sunday. They were varied – childhood recollections of her love for her sister, her memory of lying on the bathroom floor begging god to help her breathe so she would not have to disturb her parents on a night they seemed to be getting along, her ongoing battles with asthma and eczema, her yearning to be loved, her sexuality, and her bisexuality, a fact she liked to make clear by speaking and writing the word in all capital letters.

From among her writings, I chose to go to the microphone and read “A Good Day,” a piece I picked because on that day everything had gone well for her, even her doctors’ appointments. I knew from Corky that Susan’s life had been filled with illness, so I felt glad and less intrusive to share in a day she felt free of pain, a day spent with her sister joyfully. I did not feel entitled to read intimate accounts – her playful musings about masturbation, or her yearnings to have someone make love to her – not that I haven’t known both.

Robin Song opened the program by lighting a candle against a backdrop of collages and drawings Susan created. These art works clipped to twine by tiny clothespins were for friends to take as were pieces of her jewelry, her scarves, jackets and other clothes.

Robin included a ritual dropping of smooth and lovely stones into a translucent bowl of water after each woman read one of Susan’s writings. These stones, Robin said, remind us that what we give of ourselves ripples out. Our lives invariably touch other lives, whether or not we think so.

At the conclusion of the ceremony, music for dancing played through the meeting room at Strawberry Creek Lodge in North Berkeley and the women who knew and loved Susan moved as they were able in body or spirit, waving Susan’s scarves or sharing with each other the clothes they wore that had once been hers.

“i was waiting for you

holding your place

till you got well

a susan-shaped space

no other dancer

could grace

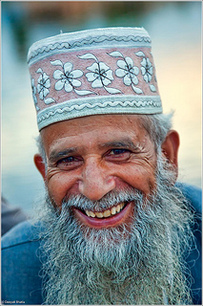

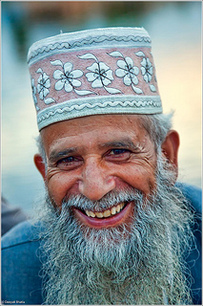

Hair Color on September 6, 2108 / Alison R. My hair has been my crowning glory, and my stylist would be the first to say so.

I came to San Francisco from Southern California and met my son and daughter-in-law’s hairdresser, Romy. Since that time I have applauded all the variations she created from July 1999 until December 2012. Only briefly, five years ago when baby Erin was born, did I go a day or two with a poppy-colored head of hair.

The joke in the hospital room when my son saw me was that if the baby went missing at the same time I left, they would send out an amber alert and I would be pulled over in a minute. Romy recognized that this was a dye job that hadn’t succeeded and scheduled a re-dye within the week. That was her only misstep in all the years she ruled my hair.

Romy’s control had been pretty absolute since we first met and she declared me drab. Mine was a history of deferring when it came to hair. Ours was a willing partnership. She did what she thought was beautiful and I agreed. While those days are over, I am ashamed to say I acted the coward one more time and didn’t tell Romy directly that I grew out the color and let another stylist cut it off. When she called me to say she missed me, I called her back and left a message. I said I had been afraid to disappoint her by going natural and that I feared she might have tried to talk me out of it. I regret not saying what I really felt.

Deciding to be less hidden beneath clever colors and artful streaking has taken years. It has only been within the last several that I accepted my aging with greater affection. I want to honor the crone I have become. This crone wants to spend less time and money on her hair and more on meditating. I want to trust my own instincts and follow my passions.

Jean Shinoda Bolen in Crones Don’t Whine says, “A crone is a juicy older woman with zest, passions, and soul.” If you aspire to be one, the secret is to be yourself while your mind, heart and body still function well enough and you appreciate being alive.

Bolen writes: “Crones don’t whine; they’re juicy and they trust their own instincts. Crones are fierce about what matters to them. They speak the truth with compassion. They listen to their bodies, reinvent themselves, and savor the good in their lives.”

She doesn’t say that crones don’t dye their hair or wear make-up or have facelifts if they think improving their appearance would make them happier or more themselves. However, I’m of the less-is-more frame of mind. The less I see myself facing the job of aging gracefully and graciously, the more I put off embracing this crone stage of my life.

I come by my vanity honestly. My hair has always been my “crowning glory.” From my earliest years when my mother took me to beauty shops to the time I first changed hair color in my mid-thirties, hair has helped to represent the “self” I want to see in the mirror and the “self” I want to present to the world.

For now, I see a woman in transition, willing to be more who she is. I like the mouse color I see in the mirror. I still rumple my hair and apply what Romy calls “product” to achieve a jaunty look. This new look reflects the energy and creativity that have brought me this far into cronedom.

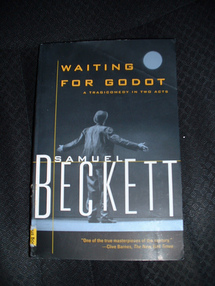

Waiting for Godot / William Wend At one time and for a long time, Samuel Beckett’s absurdist play Waiting for Godot was high on a list of literature that explained me to myself. It was up there with Shakespeare’s Hamlet and T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Liking that play was a matter of pride. I “got it.” Its absurdity spoke to me – a prideful reminder that I knew the meaninglessness of life. Friday night Corky and I saw the Marin Theater Company’s production of this play. This time the play didn’t speak to me. The play was essentially the same as the Ireland’s Gate Theatre Waiting for Godot at Cal Performances in 2006. I loved it in ’06. Same barren stage, leafless tree in the first act, scattering of hopeful leaves in the second, same moon zipping into the sky as day ends and same no-show Godot. What didn’t work on stage I leave to critics to explain. What clearly no longer speaks to me is two acts of disillusionment and hopelessness. Vladimir and Estragon, (Didi and Gogo), still expect an outside force, “Godot,” to give meaning to their sad and empty lives, and this isn’t going to happen. Meanwhile, they try to pass the time and “hold the terrible silence at bay” until Godot arrives. The play reflects a meaningless world in two acts performed on an almost empty stage and may only be performed by a male cast. The play’s director said so when I asked him if Beckett had so stipulated. When I first fell in love with the play, its unending dissatisfaction and emptiness suited me. Like Beckett after World War II, I too allowed that joy and beauty were absent in the world. Certainly, Beckett’s Europe had better reason than I to adopt a posture of weariness, but I took to absurdity and the glorification of incomprehension as expressions of my human condition. But this is not a review of the play per se. Not a critic, I generally rely on my right leg as an arbiter of engagement. It never shakes at the opera. It was still during Saturday’s ballet performance. But Friday night, I knew from the leg’s restless shifting and shaking that this theater experience wasn’t working for me. I lay the right leg over the empty chair next to me, but that was a temporary fix. Crossing it over the left didn’t help nor did crossing the left over the right. Because I was holding my former girlfriend Corky’s hand, and it rested on my left knee, I was aware that my discomfort might distract her. So what in me has changed so much that this performance of Godot left me unmoved, except for the restless shifting of my right leg? Beckett’s tragicomedy now feels more unhappy than comedic. Although I used to laugh, it was probably not at vaudevillian turns or non sequiturs as much as at the confusion I sensed in other members of the audience. On opening night in Marin, the director said 160 people came to see the play. At intermission, 37 had gone home. By Friday night when Corky and I saw the play the house was sparsely filled and 37 other theatergoers probably left at intermission. I might have gone too, but I came with Corky and she had not seen the play. In a Sunday morning conversation with my oldest son who, like me, once flirted with the void, I said I had little interest in Beckett’s tragicomedy when I saw it Friday night in Marin. I wondered if I hadn’t outgrown living without optimism and was now finding a play bereft of connection an uncompelling evening out. Having given some thought to why I was not entertained by the human suffering I saw on stage, I conclude that watching Vladimir and Estragon struggle with uncertainty and disappointment is more painful than amusing. My own grief is not something I can laugh off. To be without compassion for the human condition and to be without compassion for one’s own grief is no laughing matter.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed